Thoughts have power—sort of. A new device uses the electric energy of a person’s brainwaves to trigger a light-emitting diode, which then remotely activates light-inducible genes in a small implant placed in mice.

The system, described in Nature Communications today (November 11), may eventually provide new gene and cell-based treatment opportunities that respond to an individual’s specific mental states. Although the contraption sounds unusual, it relies on combining two well-known technologies: optogenetics, which uses light-sensitive proteins to control gene expression, and an EEG-based brain-computer interface (BCI), which harnesses the brain’s electrical potentials to create a physical output.

“This work is pretty awesome,” said synthetic biologist Timothy Lu of MIT who was not involved with the study. “This is the first time people have gone this far with combining these technologies.”

Martin Fussenegger of ETH Zurich, who led the new research, has been working on ways to remotely control gene expression for nearly a decade. His recent work has focused on creating light-inducible transgenes that can produce proteins or chemical signals within cell implants when activated by light of a specific wavelength. Because nerve impulses in the brain captured by an EEG device are electrical, this information can easily be relayed to a light source. BCIs that capture such neural inputs have been used to control cursors, prosthetic devices, or even the actions of animals in the lab. But “never before was it possible to bring brainwaves to the level of expression and controlling transcription of a gene,” said Fussenegger.

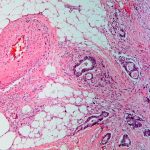

To engineer a BCI-powered optogenetic system, the researchers created a small, implantable device that contained cells responsive to near-infrared light, and a light-emitting diode that produced this wavelength. When exposed to the light, the cells produced a bacterial molecule that induced the synthesis of interferons. The cells were contained within an implanted device; secreted proteins diffused into animals’ bodies across a semi-permeable membrane, but the cells could not enter a mouse’s bloodstream.

This implant was wirelessly linked via a Bluetooth device to a monitor that captured a human participant’s brainwaves with an EEG sensor placed on their foreheads. While monitoring their brain activity, the researchers asked participants to perform one of three mental exercises: to play a focused game of Minecraft for 10 minutes; to control their brain activity in response to the brightness of a visual LED display; or to simply relax, by meditating or letting their minds wander.

“In all three mental states, the brain produced very specific [electrical] signatures,” said Fussenegger. “These EEG signatures were then converted into threshold values which turned on the LED and illuminated the cells,” which were contained within the implant on the benchtop.

The optogenetic implants were then placed under the skin of mice that moved freely on a surface that generated an electric field in response to the EEG signal from a person’s mental state. When switched on by the appropriate brainwaves, the surface transmitted the electric signal to a receiver that powered the infrared LED. With the light turned on, genes within the implant cells were expressed and proteins secreted into the mouse circulation.

Fussenegger expects the technology will be ready for human applications in another decade or so. “Smartphones have batteries that can work as a power source for the LED,” he said. “We could have a device implanted somewhere in [a patient’s] head. It would transmit via Bluetooth to a smartphone, and the phone could then power the implant.”

Such devices are “very forward-thinking,” said synthetic biologist Matthew Bennett of Rice University in Texas who was not involved with the study. “It sounds so futuristic and almost mad-scientist-like, but there might be diseases we could control . . . depending on the state of an individual’s mind.”

Treatments based on these implants could “be particularly interesting for any type of brain disease where the brain produces a pathological brainwave signature, for example in chronic pain conditions or [some forms of] epilepsy,” Fussenegger noted. Of course, he added, “it’s not meant for general conditions where you could just take a pill or push a button.”

RSS